Photo by Suyash Ukidve

As we are now in the dry season of the year, news will start pouring in about forest fires in different parts of India. This is an every year story when there is some or the other fire in the months of November to May, in some part of the country. Forest fires are horrible, they totally disrupt the ecosystem and all the life there- this is what we’ve been seeing in the news and learning since our childhood. Is this entirely true though? Or is it just a misunderstanding?

Now you might be thinking, how can something so evident be a misunderstanding? We can literally see everything burning down to ashes! Well, this is what this blog is about. Research says that we’ve been looking at Forest Fires all wrong and this is what we’ll be discussing in this blog.

Note that whatever you’ll be reading in this blog will probably be totally contradictory to whatever we all have been learning since childhood or seeing all over the media. Also note that these are not my own opinions or thoughts but actual research carried out by ecologists. Even if you’re not a nature geek, it won’t be boring and you’ll be learning something totally new (and maybe surprising), so keep going!

A very important thing before we get started- make sure you’ve read my previous blog called “Savannahs, in India?” This blog would make complete sense to you ONLY if you’ve read that blog. So go check it out first, if you haven’t already- https://kswild.video.blog/2021/01/14/savannahs-in-india/

Assuming that you’ve all read my previous blog, let’s get started.

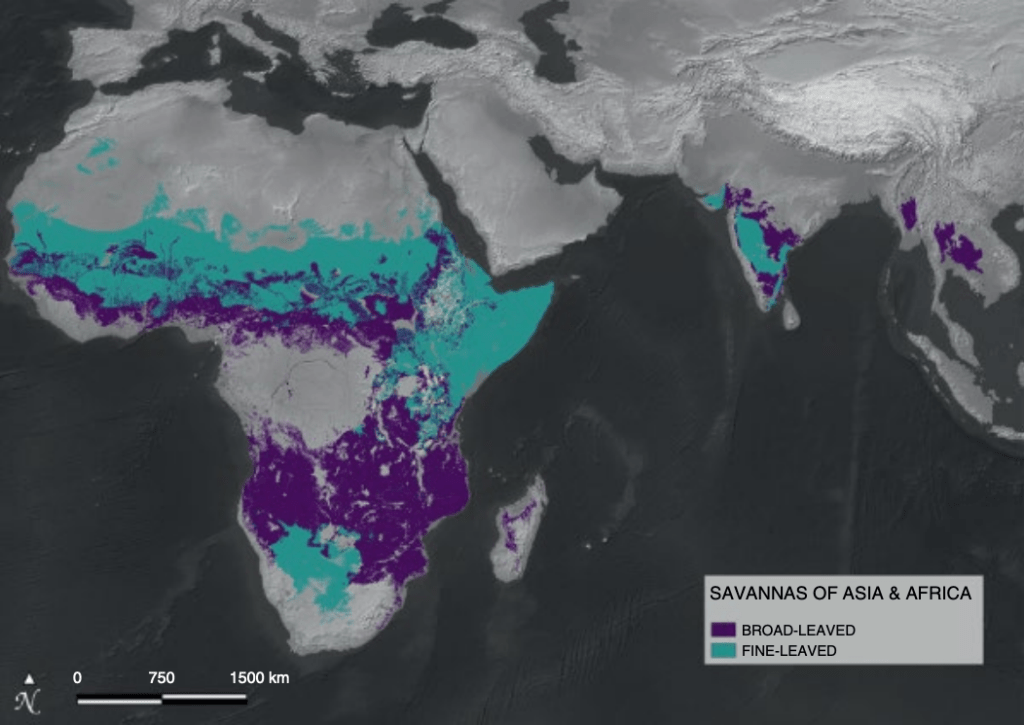

It is believed that forest fires came into existence only when humans started using fire. However, a common source of fire that we often ignore is lightning. Lightning has been causing fires since almost the past 10 million years, even before humans first used it. Fires have been shaping India’s landscape since ages. In India, fires have been most active in our Savannahs(now you know what regions I’m talking about, this is what we discussed in the last blog). Indian Savannahs as well as Savannahs all over the world have evolved with regular fires since millions of years.

The indigenous people of India have long used (and still do) fire as an essential land management tool. Among many other reasons, they burnt off the grasslands in the dry season to promote the growth of fresh fodder for their livestock. These practices were carried out since ancient times, which benefited both the ecosystem as well as the people who co-existed there. However, this traditional knowledge of the people was at odds with the colonial view. As we discussed in the last blog, the Britishers were only interested in Timber and other such forest extracts- basically trees, and how they had classified the Indian Savannahs into either Deciduous Forests or Wastelands. Fires hinder the tree growth by top killing trees and promoting grasses. The colonial foresters were trained in western silvicultural practices where fire indeed proved to be destructive for tree growth. They applied the same assumptions in India and banned all the traditional fire regimes of the locals. This belief of all fires are bad was carried forward post independence and all fires were declared as illegal in the constitution. The 50,000 year old tradition of controlled burning was forgotten.

This was the historical point of view of why we in India view fires as bad, even though they have been prevalent in the subcontinent since ever and have played a crucial role in the shaping of our landscape. It is interesting to note that in many other countries, Savannahs are burnt regularly- the Prairies of the USA, the Australian Eucalypt Savannahs and even the African Savannahs burn.

Forest fires or Savannah fires?

The term ‘Forest Fires’ is problematic. In the last blog, we discussed how forests are different from Savannahs and how we’ve got Savannahs in almost the entire Indian peninsular region. When there is a fire in a forest, it indeed is destructive and destroys forest biodiversity that is typically not adapted to fires. So in that sense, Forest Fires are not at all desirable and need to be stopped. For example, the Amazon Fires are undesirable and so are fires in Mahabaleshwar. However, we do need regular fires in Savannahs. That’s the catch! Referring to Savannahs as Forests changes the management perspectives as both are different ecosystems. Fires in Savannahs shouldn’t be called ‘Forest Fires’. Let’s call them ‘Savannah Fires’ instead.

So, let us now discuss the importance of fires and why even today, we need regular Savannah Fires.

As the Savannahs have evolved with regular fires since the past 10 million years, the plants that belong to this ecosystem have also evolved and adapted to the fire. Typical Savannah plant species are like icebergs- there’s much more to them under the ground than what we see just on the surface. They have a large chain of roots and organs under the ground that have developed over ages. Savannah species are very prone to fires as they store volatile oils in them that promote fires during the dry season. In the event of a fire, everything on the surface burns off, but the plants are very much alive under the ground as soil is a very good insulator. The fires clear off the surface making space for new growth, which helps the plants to re-sprout immediately. In fact, there are many Savannah species that depend on the heat of the fire to re-sprout, in the absence of which they wouldn’t grow. Fires also activate the dormant seeds underground to germinate. This is how the Savannahs are dependent on regular fires.

(1) Regrowth of fresh vegetation after burning of a small patch, just in a weeks time. (2) 3 weeks after burning

As we discussed in the previous blog, Savannahs have an open canopy that allows the growth of grassy species on the ground. In an event of dense trees growing and closing the canopy, the grassy understory would die resulting in the extinction of several species. Fires keep a check on this and do not allow woody encroachment in the Savannahs. The woody plants of the Savannahs have also evolved with the regular fires. They have a much thicker bark than forest trees to survive fires. During fires, these trees do not die, but fires don’t allow them to grow very tall as well as propagate all over the area, to maintain the open canopy. This mechanism has evolved over millions of years that has been regulating and naturally maintaining our Savannahs. If fires are totally suppressed, there would be woody encroachments all over the Savannahs which will totally change the ecosystem.

These Acacia trees here are probably 50-100 years+ old, yet they are very short as the fires haven’t allowed them to grow tall

Another important role that fires play is keeping invasive plant species at bay. Take for example the invasive plant Lantana camara. This plant originally belongs to South and Central America but is dominating the Indian landscapes today causing trouble to the native species. Before the Brits arrived, invasive species such as this one were kept under control by regular fires as fires kill these encroaching species. However today as fires are suppressed by the government and are declared as illegal, this invasive plant along with other invasives like Cosmos have dominated the landscape and are proving to be very competitive with the native species.

This is why Savannahs even today need regular fires. Let us now understand what will happen if fires are not allowed.

As we discussed earlier, a lot of typical Savannah plant species are dependent on fire for their growth. We’ll lose out on all those plant species if fires are suppressed. Many of the endemic plant species will be lost resulting in the decline of some herbivore species which will directly affect the predatory animals like tigers. Suppression of fires will also allow the growth of invasive plant species and dense wooded trees which will affect the ecosystem and its inhabitants negatively. When there are regular fires in Savannahs, the dead plants get burnt off clearing the land for new growth. The height of this fire is just surface level and can be controlled easily. However if fires are stopped, the dead plants will get accumulated over the years. As these dead plants get accumulated, the fuels just pile up, waiting to get burnt- and they sure will burn one day. But the flames would be so tall that it would be beyond control. This is what we call crown fires.

A recent example of huge crown fires in India are the Bandipur fires of 2019. Bandipur National Park is a typical Wooded Savannah region, which is of course wrongly classified as a Deciduous Forest like all the other Wooded Savannahs of India. Since it is a protected region, fires there are totally suppressed by the government. As a result, fuels got accumulated and invasive species like Lantana camara bloomed over the entire region. A massive fire broke in various parts of Bandipur in 2019 which got out of control, burning the entire Savannah. Events like these can be easily avoided by letting the region burn periodically.

What happens to the animals of the Savannah when it burns?

Like the plants, the Savannah animals too have adapted to the fires since millenia. The animals that we see in Savannahs are typical Savannah animals that can only survive there and have been evolving with the ecosystem and the fires over ages. The fires don’t harm them at all as they have their own survival strategies. The reptiles and amphibians can burrow and the birds and mammals can flee to some other unburnt area till the fires cool off (since fires are typically patchy). If fires were to kill these animals, we would not see such a vast diversity of endemic Savannah animals today. And not to forget that the fresh forage after the fires supports many herbivores.

What about the Carbon dioxide that these fires release?

Fires of course release Carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But in the long term, Savannahs as an ecosystem store far more carbon than they emit. That is, Savannahs are a net carbon sink. We all know that forests play a huge role in Carbon sequestration. However, what most people are not aware of is that Savannahs also play a huge role as carbon sinks, even though they might look barren to us. Savannah plant species store a huge amount of Carbon in their underground organs and are equally important Carbon sinks as are forests. Also, the ash and char that is left behind after burning is essentially carbon that gets mixed up with the soil- an under appreciated carbon sequestration process.

If Savannahs used to burn naturally in ancient times, why do people burn them themselves, now? Isn’t that human intervention?

Savannahs have been burning on their own since ancient times. Even today, a significant number of fires in Savannahs all over the world including India are started by lightning. As humans evolved, they changed the landscape with them. Earlier, there were long, continuous, uninterrupted stretches of Savannahs that used to burn entirely even when a small fire started. But as humans evolved, these long patches got fragmented. Even a small rabbit track through the Savannah is enough to stop the spread of fire. In India, there are fragmented patches of Savannahs in urban cities or around villages, the hills in Pune city for example. These patches cannot burn entirely as the continuity of the Savannahs is broken due to many reasons. Therefore, burning these patches manually in a controlled environment is necessary. Infact, Savannahs worldwide are burnt regularly by the means of ‘Prescribed Fires’. Prescribed Fires are the fires that are set in the Savannahs with a clear management goal (eg. fresh forage) after carrying out a detailed study of the weather, the winds, the vastness of the area and some other factors before setting a fire. That way, the Savannahs are burnt in patches, in a controlled environment. That’s how the locals of Indian Savannahs have been burning them since ages.

How often do Savannahs need to burn?

There’s no one answer to this. It depends from region to region. Some Savannahs need to burn more frequently than the others. The goal should be to meet the ‘natural’ burning frequency of the particular Savannahs like it was millions of years ago. The associated biodiversity of these Savannahs has evolved with this historical fire frequency and any drastic changes to this will typically have negative effects on the native biodiversity. Over burning is not good, under burning/not burning is even bad. More research needs to be carried out from region to region to plan proper fire regimes.

Now that we know that Savannahs need to burn, do we just go out and burn them?

No, not at all. As we discussed, to burn a particular patch of a Savannah a lot of research has to be carried out beforehand- what we call ‘Prescribed Fires’. Only the people trained in Prescribed Fires should be permitted legally to burn the Savannahs. This also includes indeginous people who have such training, though in an informal way. Burning the Savannahs is not something that we do for fun, a lot can go wrong if it is not done carefully.

So to conclude, it is important for us to understand that Savannahs have evolved with regular fires over millions of years and fires are an integral part of the Savannah ecosystem. Stopping these fires will negatively affect this ecosystem and all its inhabitants. To keep the Savannahs as they are and to protect this unique ecosystem, allowing them to burn is essential. However, the government has declared fires as illegal in the country, especially in all the constitutionally protected regions like national parks and sanctuaries. As we discussed in the previous blog, many of these regions are essentially Savannahs even though they are wrongly classified as Deciduous Forests. The government spends huge amounts to suppress fires all over the country. This has been changing the Savannah ecosystems drastically. There have been a lot of woody encroachments and invasion of foreign plants, especially Lantana camara and we’ve also lost many of our Savannah endemics. Our government is ready to spend a huge amount of money to remove Lantana, but a simple answer to this is allowing fires to do their job. Fires have been widely misunderstood and today we even have sufficient research to prove that we need to allow regular fires in our Indian Savannahs. It’s high time we realise that and normalise fires as well as change our plan of action. As it is popularly said, if you do not burn the Savannahs, they will burn themselves.

———————————————————————-

Thank you for sticking to the end, hope you learnt something new. Thanks a lot to my friend Ashish Nerlekar for his help with this blog.

As always, you can get in touch with me if you have any queries or want to have a discussion. Just comment below or DM me on Instagram ‘@ks_wild’ and I’ll get back to you.

———————————————————————-

Here are some references that you can go through to get a deeper insight about the importance of fires in the Indian Landscape :

- An article about the fires in India- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318122947_Notes_from_the_Other_Side_of_a_Forest_Fire-

- Bandipur Megafire 2019- https://scroll.in/article/916442/indias-understanding-of-forest-fires-has-been-skewed-by-colonial-era-policy

- https://www.thehindu.com/sci-tech/energy-and-environment/fires-are-a-crucial-component-of-some-forest-systems-says-group-of-scientists/article26431398.ece

- A talk on Fires in the Indian Landscape- https://www.instagram.com/tv/CBUma5yAFxw/…